There was no pastoral industry in the Mitchell River landscape prior to the 1890s. The Jardine brothers passed through the area in 1865, with a herd of cattle, on their way to the Somerset pastoral property in northern Cape York Peninsula. This expedition led to hostile encounters with local people and loss of life on both sides. The Dunbar pastoral lease was then taken up in 1882, Koolatah in 1886, Rutland Plains in 1895 and the Mitchell River Mission was established in 1904 under the ‘Aboriginal Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act’ (Queensland 1897).

There were as many as 700 people living in the lower Mitchell River valley in the early 1930s (Trump 1935). The landscape had a dense toponymy of place names at that time.

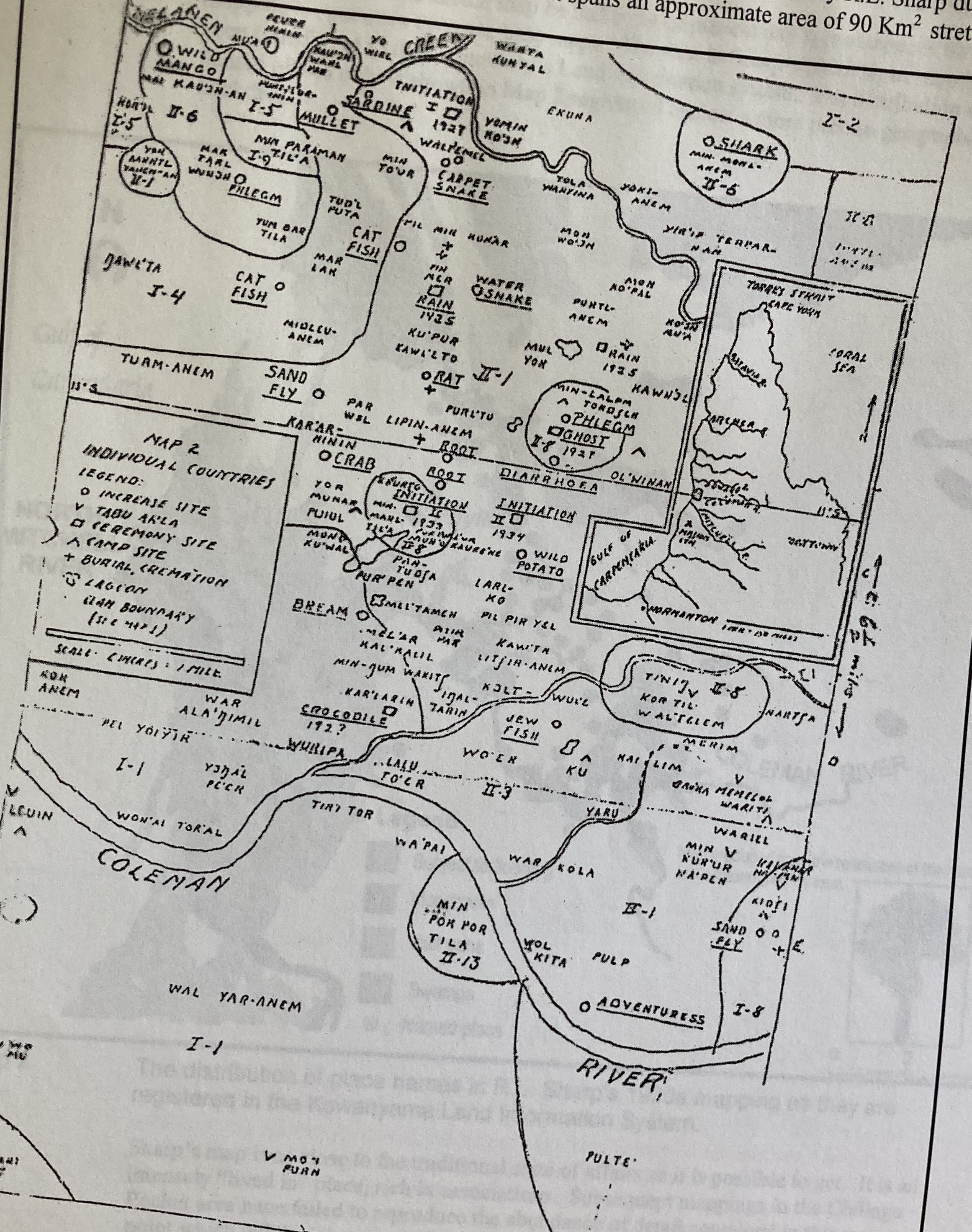

Figure 1. Place names mapped by Lauriston Sharp in Chillagoe Pocket (1937)

Figure 1 shows a map of 89 placenames recorded by Lauriston Sharp in Chillagoe Pocket in 1937. This area is in Yir Yoront country between the Mitchell and Coleman rivers, immediately to the north of Kowanyama and within the Pormpuraaw community area. By the 1990s only 25 placenames were recorded in approximately the same area (Cordell and David 1993, Taylor 2004). These place names record ‘increase’ or ‘poison’ sites that are important in natural resource management, conception and creation sites; and, story places which usually refer to the actions of mythical creatures in the landscape.

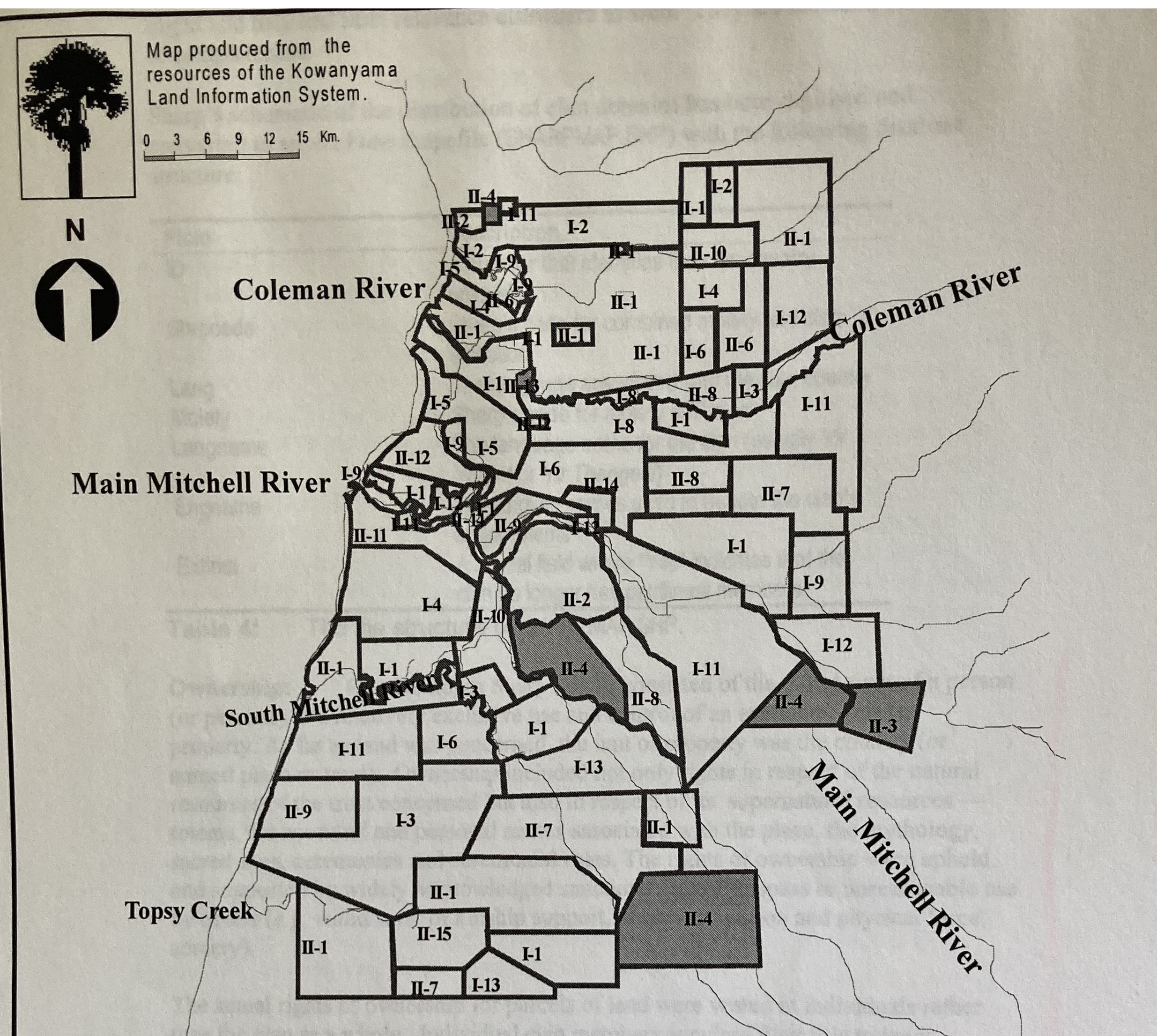

Figure 2. Clan domains mapped by Lauriston Sharp (1934) in the Lower Mitchell River valley (reproduced by Taylor 2004)

Figure 2 covers the present day Kowanyama area and parts of surrounding properties. It shows a schematic map of clan 'estate’ or ‘domain’ extents in the lower Mitchell river valley that was composed by Lauriston Sharp (1937, 1952). These domains were controlled by groups of kin-related people or clans who had ownership rights through totemic or concept affiliation which is sourced at special places in the landscape that have totem names (duck, emu, rain etc.). This system conferred primary rights of custodianship; and secondary rights of access to a domain and its resources (such as for hunting, fishing) on any individual. Any person may only exercise one primary right to a domain but can hold a number of secondary rights to other domains elsewhere in the landscape.

The domain boundaries in Figure 2 are approximate and have no physical expression in the landscape. Twenty-two of the mapped domains cover the approximate extent of present day homeland sites, of which, as of 2007, there were nineteen (with another six under consideration). Of these actively occupied homeland sites, three have leaders who are in their mother’s country and the remainder have leaders who are in their father’s country (patrilineal affiliation).

There is a concordance topologically between the two distributions with present day homelands representing ‘focal places’ within the area of the clan domain system represented by Sharp. The toponomy of traditional names (Figure 1) may not be so obvious in discourse between people today but the principle of patrilineal affiliation persists very strongly in relation to the membership and organisation of present-day homeland sites. Nowadays, family/patrilineal affiliation to country is expressed by refrence to a homeland site name ('Scrubby bore mob') or a homeland leader's name ('Alma's mob'). The latter place also has a Kunjen name (I'ygow') and a pastoral name ('Shelfo').

Figure 3. Notice of a closure of homeland country following a death

Figure 3 shows a public notice of a funeral closure of a homeland posted for the bereaved families by the Land Office (KLNRMO) in Kowanyama. It requests that people keep away from the homeland country until enough time has elapsed for the spirit of a recently deceased person to return to their special 'conception' or 'spirit' place. This is an example of the exercise of moral and spiritual authority in the mythical properties of the landscape by a homeland leader which traditionally belonged in the clan domain described by Sharp in the 1930s and represented in Figure 1.